Commemoration days: January 18 (31), May 2 (15)

Biography

Childhood and Youth

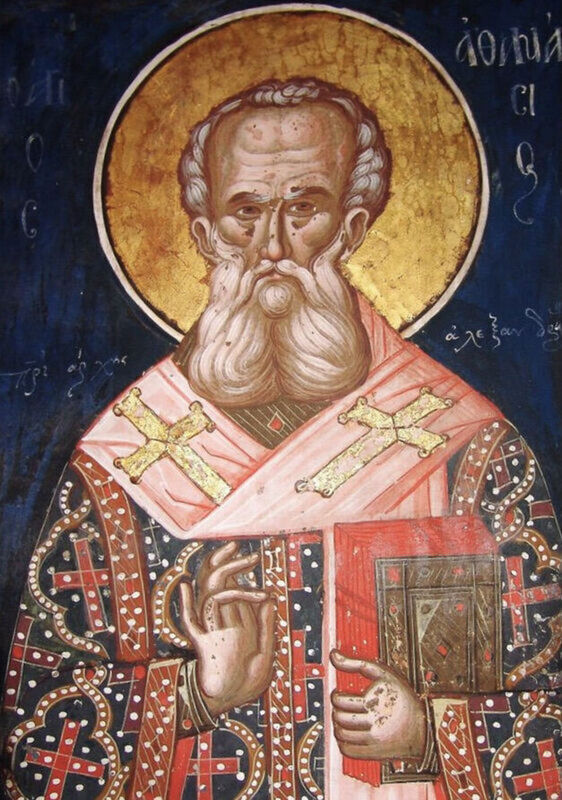

Athanasius of Alexandria is revered by the Church as an outstanding ecclesiastical writer, a great hierarch, and a defender of the purity of Orthodox doctrine.

Little is known with certainty about Athanasius’ parents, the exact date of his birth, or his early years.

According to some accounts, as a child, he "baptized" his peers while playing. However, when the local bishop learned of this, after careful consideration, he recognized these baptisms as valid. It is difficult to say how much truth this legend holds, and there is no definitive basis to accept it as fact.

It is known that the saint’s childhood coincided with the era of bloody persecutions against Christians. Perhaps he or his parents (if they were Christians) experienced the consequences of Diocletian’s persecution firsthand.

His broad knowledge of general subjects as well as Christian faith and morals suggests that in his youth, Athanasius received an excellent secular education and was well-instructed in the truths of Holy Scripture and Tradition.

He joined the clergy of the Alexandrian Church at an early age. For six years, he served as a reader and was later ordained a deacon. This period of his life coincided with the spread of one of the most dangerous and destructive heresies—Arianism.

Athanasius was spiritually close to Bishop Alexander of Alexandria, and when the latter attended the First Ecumenical Council, he took Athanasius with him.

Episcopal Ministry

After the death of Bishop Alexander (estimated to be around 326 or 328), Athanasius succeeded to the vacant see of Alexandria. By that time, he was already known as a man of steadfast faith.

His ideological opponents, the Arians, later claimed that he had been elected in violation of canonical rules and by a minority vote, but this was untrue. Lies and slander were among the most common tactics used by the heretics against Athanasius. Subsequently, they leveled increasingly absurd accusations against him.

In addition to the challenges posed by the struggle against Arianism, the saint also had to deal with the consequences of the Meletian schism.

Some time after the First Ecumenical Council, the Arian-leaning hierarchs, feigning humility and formally expressing agreement with the teaching of the Universal Church, gained favor with Emperor Constantine and secured permission to return from exile.

Eusebius of Nicomedia, seizing the opportunity, urged Athanasius of Alexandria to receive into communion the founder of the heresy—the blasphemous and impious heretic Arius. As expected, the saint refused, fully aware that the Arians' claims of agreement with the Church were merely words.

Then the Eusebians openly turned against him, joining forces with the Meletians. Realizing that theological debate with the orthodox hierarch was futile—as it would expose their true stance on the Nicene Creed—they focused instead on discrediting his character.

To this end, they resorted to fabricated and outlandish accusations: that Athanasius illegally imposed a linen tax on the Egyptians; that he supplied gold to the conspirator and rebel Philumenus; that he engaged in immoral and licentious behavior; and that he committed sacrilege (allegedly ordering the beating of Presbyter Ischyras, overturning an altar, breaking a chalice, and burning sacred books).

Under these attacks, Athanasius was compelled to meet with the emperor in person, which he did. Contrary to the heretics’ hopes, he managed to justify himself and expose the absurdity of these baseless accusations.

Yet, Athanasius’ enemies were not quick to abandon their hatred and hostility. This time, they devised a more elaborate accusation: they spread a bizarre rumor that Athanasius had murdered Bishop Arsenius. As "proof," they displayed the hand of the "murdered" hierarch—despite the fact that Bishop Arsenius was actually alive, hiding in a remote monastery.

Condemnation and Persecution

Despite the obvious falsity of the accusations, a shadow was cast over the Alexandrian hierarch. Soon, his enemies persuaded the emperor to summon Athanasius to the Council of Tyre, where—given the hostile disposition of most participants—nothing good could be expected. And so it happened. Athanasius of Alexandria was deposed from his see and condemned to exile.

Meanwhile, in November 335, he was solemnly received in Tyre. From exile, he wrote to his flock, while the faithful, in turn, did not cease their efforts to secure the return of their beloved hierarch.

In 336, Arius died under mysterious circumstances—an event believers regarded as the judgment of God’s justice—and in 337, Emperor Constantine also passed away.

Return from Exile

Following these events, Athanasius was restored to the Alexandrian see through the efforts of Constantine the Younger. On his way back, he met with Emperor Constantius. The people of Alexandria greeted him with joyful shouts.

But the Arians and Meletians once again burned with desire to depose the saint. This time, they accused him of ascending to the Alexandrian throne without a formal conciliar decision, solely by imperial permission.

St. Athanasius convened a council of nearly 100 bishops, which dismissed the accusations. Yet the Arians refused to relent and continued their scheming.

The Eusebians, who had formed a council in Antioch around 340, elected another bishop, Gregory of Cappadocia, to the Alexandrian see. He was then installed with the help of civil authorities and military force.

Athanasius was forced into hiding. At first, he concealed himself near Alexandria, then fled to Rome, where the local council of 341 acquitted and vindicated him. He spent about three years there, maintaining contact with his flock.

In 343, he traveled to Gaul and then to the Council of Serdica, which reaffirmed his innocence. Yet he could not return, as the Eusebians, having turned Emperor Constantius against him, secured a ban on his restoration.

Only in 345, after the death of Gregory of Cappadocia, did Constantius—urged by Athanasius’ supporters—allow his return to Alexandria. In October 346, the long-suffering saint arrived in the city.

Renewed Persecution

A few years later, especially after 353, due to shifting political circumstances, persecution flared up again. In 357, the see of Alexandria was handed over to the Arian heretic George of Cappadocia.

Athanasius was forced into semi-clandestine existence. Imperial authorities hunted him everywhere, but he managed to evade capture, moving from place to place.

The situation improved after 361, with the death of Emperor Constantius and the murder of George of Cappadocia.

The following year, St. Athanasius returned to his see once more. He labored tirelessly to cleanse the Church from the aftermath of Arian violence.

However, the new ruler, Julian the Apostate, did not wish to see such a strong shepherd in Alexandria. In 362, Athanasius again left the city, becoming a wanderer once more.

After Julian’s death, Jovian ascended the throne. Athanasius was reinstated, but soon Jovian died, and Valens—a sympathizer of the Arians—took power. Persecution of Orthodox bishops began anew.

Athanasius left Alexandria again and went into hiding. Yet public unrest forced Valens to permit his return and order that he be left in peace.

Final Years and Repose

In 366, Athanasius was triumphantly welcomed back by the Alexandrians.

The remaining years of his life were devoted to shepherding his flock and strengthening Orthodoxy. The saint’s heart stopped on May 2 (possibly during the night of May 2–3) in the year 373.